As the Celtics’ greats pass away, trips down memory lane have become more difficult. On the other hand, the current generation is forging its own way.

Bill Walton Revived and Concluded His N.B.A. Career With Boston Celtics!

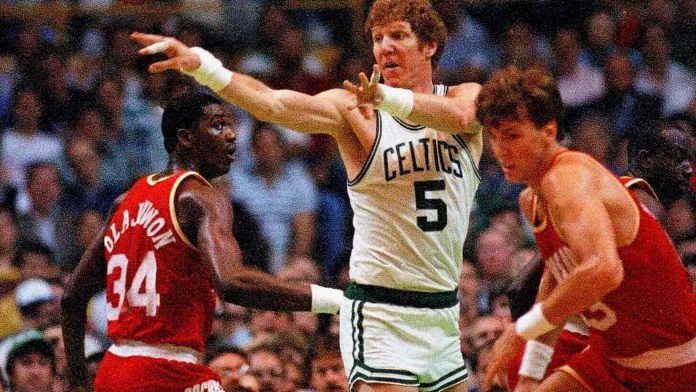

When Bill Walton was resurrected and finished his NBA career with the Boston Celtics, he devised a strategy to avoid the city’s notoriously congested traffic on game nights: he took the train to work. Walton resided in the neighborhood throughout the Celtics’ 1985-86 championship season and the 1986-87 N.B.A. finals loss to the Los Angeles Lakers.

The old Boston Garden was demolished in 1995, and the TD Garden was built in its stead. The T’s trolley cars clatter through tunnels ancient enough for archaeological investigations to reach the busy North Station commuter center.

The iconic parquet playing surface still exists, along with a few relics from the original Garden, like the now-retired jersey banners, a slew of ruddy-faced ushers with Southie accents, and ticket scalpers hidden in plain sight out on Causeway Street.

To that end, when the NBA finals return to Boston for the first time since 2010 — with the Golden State Warriors hosting Game 3 on Wednesday night — it will be the league’s version of strolling through the somewhat gentrified but still old neighborhood, making the nostalgic rounds of where it grew up.

Professional basketball did not become a popular ticket in Boston, or anyplace else in the United States, until years after the Bill Russell-era Celtics won 11 championships from 1957 to 1969. The NBA, though, mostly evolved from crawl to walk at North Station, that center of awkward urban planning.

The losses of the Retired Number Celtics have been devastating and significant for those who remain from Boston’s unrivaled historic heyday. No. 17 John Havlicek died in 2019; Tom Heinsohn (15), K.C. Jones (25), and Sam Jones (24) died in 2020; Jo Jo White (10), a 1970s great on two championship teams, died in 2018.

The new conference’s most valuable player trophy, named after Larry Bird, was then presented to the Celtics’ rising star, Jayson Tatum.

The 1980s Bird-era Celtics were our introduction to living Celtics history for a generation of sports writers too young to have covered the Celtics’ patriarch Red Auerbach lighting victory cigars from his coaching perch.

We sat on third-grade seats along the baselines, watching the Lakers and Celtics drastically enhance the league’s profile through the prism of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird’s rivalry. Reporters from out of town slept at a new chain hotel near Copley Square, where they were awoken by deafening alarms that we assumed were the work of Auerbach – because the Lakers also stayed there.

We shuddered as ecstatic Celtics supporters stormed the floor following Game 7 of the 1984 championships, wondering if Bird and company — let alone the Lakers — would make it out alive. We were at risk of suffocating or being crushed in the poorly ventilated visitors’ changing facilities, which were no match for the swarming news media.

We strolled out of the building, fatigued from the stifling late-spring humidity and evading the occasional mouse, yet thinking there was no else we’d rather be.

Those Celtics did not represent all of Boston, despite Walton’s memory of everyone being on board the ringing T. The Celtics were regarded as the reputed holdout in a league increasingly dominated by African American talent, thanks to their massive good fortune in landing Bird (retired No. 33) in the college draught and smartly trading for the rights to Kevin McHale (32), but also by stocking their bench with fringe white players. The 76ers of Julius Erving and the Lakers of Magic Johnson were the teams of choice in Boston’s black communities.

It’s easy to exaggerate parallels to past winners, especially when you consider that the Celtics have only won one title since 1986. However, some have pointed out that Marcus Smart, the tough point guard, reminds them of K.C. Jones and Dennis Johnson, Bird’s 1980s running partner (retired No. 3). While Tatum may never be considered Bird by the Boston public, he looks set to have his number, 0, joins Robert Parish’s 00 in the rafters at the age of 24.

Robert Williams III, the current center, is no Russell (retired No. 6), but he is a true, native rim protector at the age of 24. Horford, who looks a lot like Paul Silas from the 1970s, was re-signed the last off-season, and he’s the sort of savvy team-building acquisition the Celtics were known for over four decades of many championships.

After losing Gordon Hayward, the greatest player they signed, to free agency in 2020, and Kyrie Irving, the best player they traded for, to free agency in 2019, the Celtics were essentially put together like any Auerbach club. Danny Ainge, the previous general manager, performed the heavy lifting with a lot of help from the Nets, who got Tatum and his co-star, Jaylen Brown, in a 2013 trade for the withering Pierce and Garnett.

Following Kevin Durant‘s departure in 2019, the current Warriors are also built without the advantage of a boutique free agent.

This storyline is a refreshing departure from the idea of wilful stars deciding competition balance, a tactic that has irritated some fans and been viewed as destructive to the league by others.

These Celtics, of course, play in the same 3-point shooting cosmos that has been aesthetically extended more than anybody by Golden State’s Stephen Curry, another tendency that many older fans find distasteful.

And, with increased gastronomic pleasures and the normal in-game experience of floor-show gimmickry and relentless loudness that once made Auerbach’s head and cigar explode, TD Garden is no different from other N.B.A. stadiums.

Read More :

- The Denver Broncos Have Reached An Agreement To Sell The Team For $4.65 Billion!

- Gary Payton II’s Return Adds A New Layer For The Warriors!!

- Darvin Ham New Los Angeles Lakers Coach!!